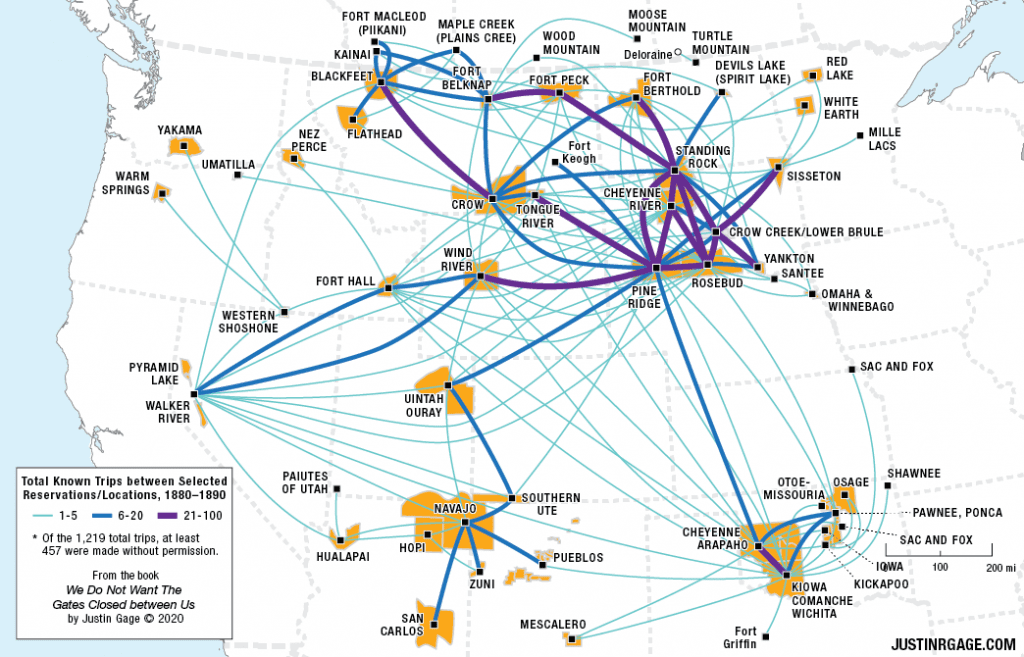

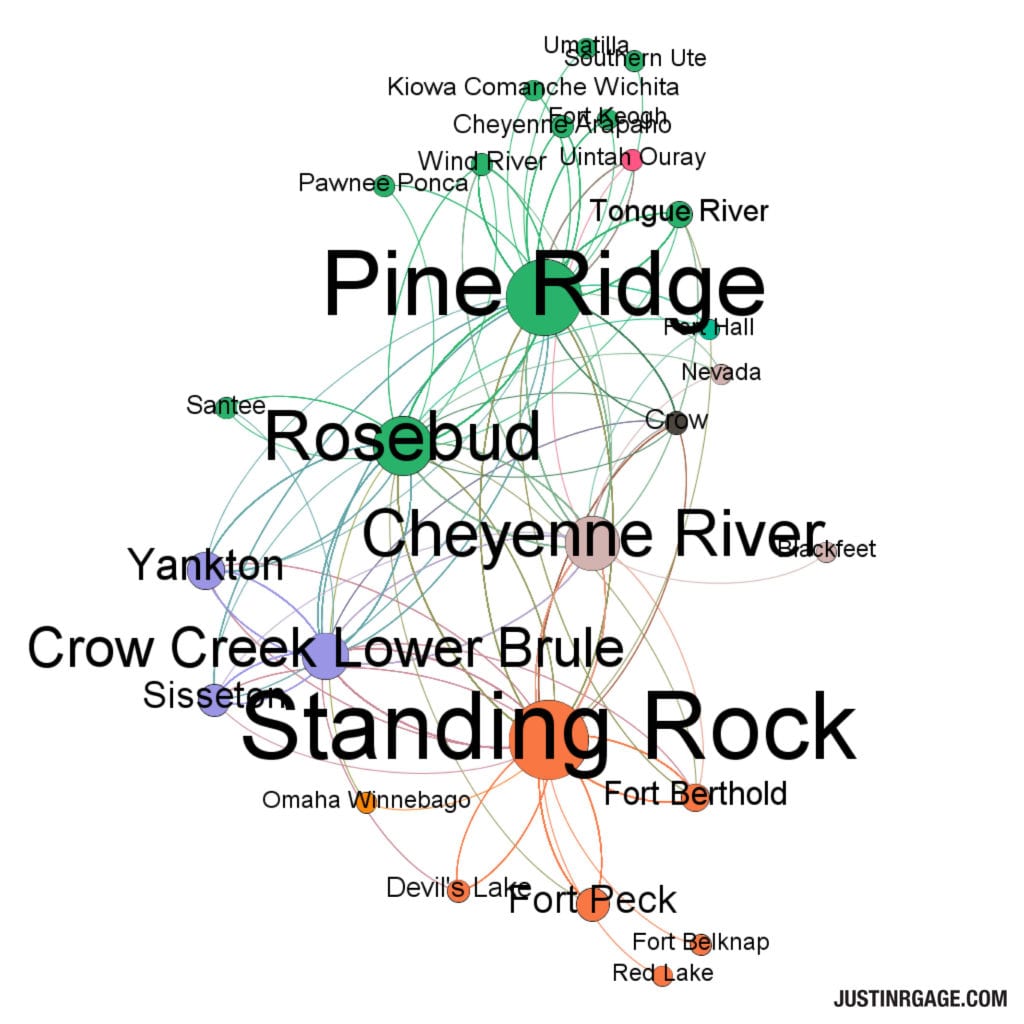

The analysis of Lakota visitation networks demonstrates that Lakotas were able to maintain the social and political bonds that tied the larger Lakota bands and smaller tiyospaye together before the reservation years. These connections were maintained despite the isolation caused by the reservation system and the limitations applied to Lakota movement off their reservations. Because of the importance of the social and kinship networks among the seven bands, the Oglalas (Oglála), Brulés (Upper and Lower Sičhánǧu), Miniconjous (Mnikȟówožu), Sans Arcs (Itázipčho), Two Kettles (Oóhenumpa), Sihásapas, and Hunkpapas (Húŋkpapȟa), Lakotas fought to preserve their right to move about and visit those living at distant localities, agencies, or reservations. Visiting served important social, economic, political, and religious purposes. There is a record of at least 468 trips made by Lakotas from one of the five Lakota agencies/reservations (Cheyenne River, Lower Brule, Pine Ridge, Rosebud, and Standing Rock) to another from 1880 through 1890. Around one third of those trips was made without permission, but many more were undetected, thus unrecorded by U.S. government officials. At least three hundred more trips were made by Lakotas to twenty-three other, non-Lakota reservations during that period, many creating new connections with tribes that they had little contact with or were hostile with before the reservation era.