Written correspondence was also used to express disagreements between

western nations and perhaps hash out those

conflicts. Intertribal relations in

the West were

complicated by long histories of competition for resources,

raiding, violence,

and alliance making. Relations were

further complicated in the 1860s and

1870s with the increased presence of white Americans in the West, the settlement

of reservations, and the constant pressures of colonialism. Tribes

were forced onto reserves, and some found themselves with new neighbors, tribes that might have been longtime enemies or distant strangers. Osages,

for instance, were

forced to relocate onto a reserve in Indian Territory in

1870, a territory with eventually more than two dozen other tribal nations,

several of which were

rivals. Like other nations in the territory, Osages had

to consider other groups diplomatically and figure out the best path toward

harmony. An early reservation-era

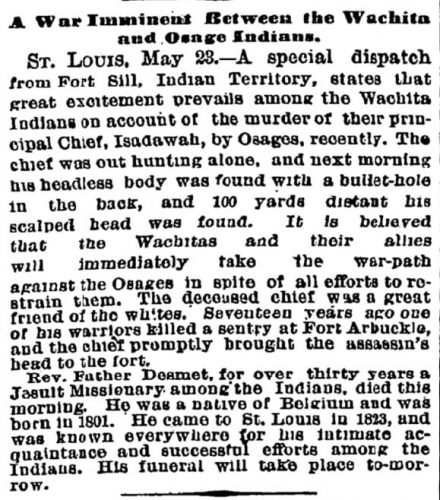

letter, sent in 1873 from Osages to Wichitas,

was an attempt to solve a dispute stemming from the murder of Wichita

chief Isadawah by a couple

of Osages. Wichitas wanted the Osages to

hand over the men responsible, and according to the white press, war

was “imminent” between the two tribes in May 1873. Shawnees who

lived Indian Territory, having gotten a copy of the Osage letter, sent their

own letter to the Osages in June that demanded the men be handed over. The Sac and Foxes did the same. Eventually a council was held, and the

Osages begrudgingly agreed to pay for Isadawah’s life with ponies.