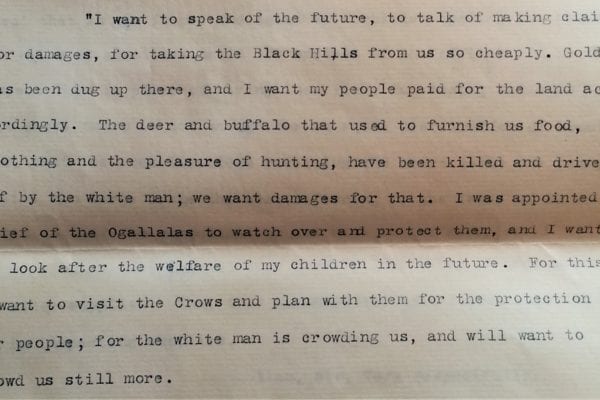

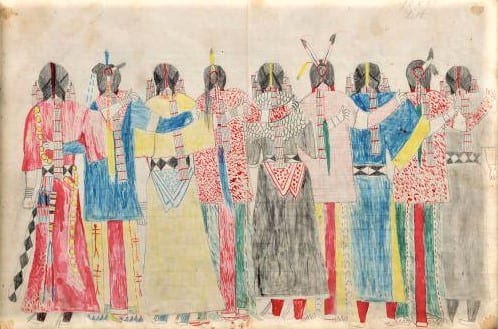

For federal policy makers, however, dancing only served to remind Indians

of their prereservation lives. It was a practice of the past, a “demoralizing influence” that detoured the path of progress.

For an agent at Devil’s

Lake, visiting parties brought dances, and the dances brought out the “paint and

feathers,” the bodily decorations of the uncivilized. Government officials, missionaries, and reformers included antidancing rhetoric in their civilizing

campaigns because dances were

the expression and promotion of so-called uncivilized, non-Christian ideas. Like the information spread by Indians in order to subvert colonial control, Indigenous religious concepts were also

thought to be damaging to the US government’s efforts. There

was

little

concern for the First Amendment rights of Native Americans because

they were

not US citizens, and policy makers limited

Native dancing for the

sake of white sensibility. It was not until

1978’s American Indian Religious

Freedom Act that government interference with the exercise of Indigenous

religious belief was deemed illegal by Congress. But back in 1883, commissioner

of Indian affairs Hiram Price opined that there

was “no good reason

why an Indian should be permitted to indulge in practices which are alike repugnant to common decency and morality; and the preservation of good

order on the reservations demands that some active measures

should be

taken to discourage and, if possible,

put a stop to the demoralizing influence

of heathenish rites.”