Thousands of Indians living on reservations in the Dakotas, Wyoming,

Montana, Idaho, Nevada, Nebraska, Iowa, and Indian Territory (excluding

the Five Civilized Tribes) learned how to read in the 1880s, according to

Indian affairs estimates. By 1889, nearly 12,000 Lakotas, Santees, Yanktons,

Yanktonais, Mandans, Assiniboines, Gros Ventres, Utes, Paiutes, Shoshones,

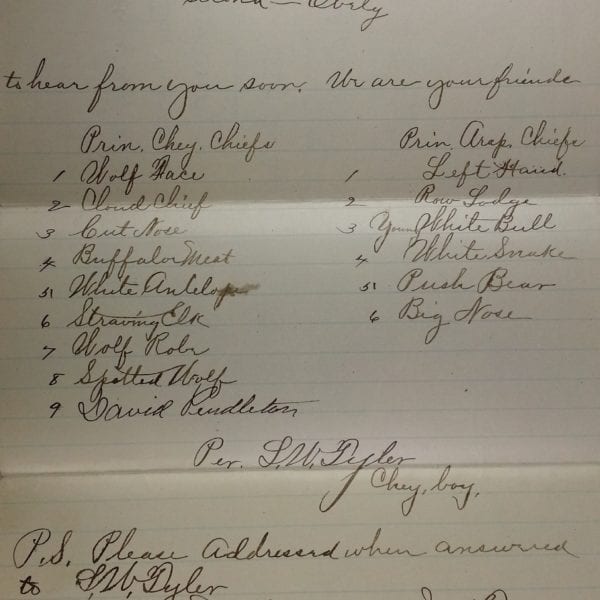

Bannocks, Arapahos, Cheyennes, Kiowas, Comanches, Apaches, Wichitas,

Poncas, Pawnees, Otoes, Sac and Fox, Nez Perce, Blackfeet, Crows,

Omahas, Winnebagos, and others

could read in English

or their Native language. Only nine years earlier,

fewer than 3,500 could read. Only

4 percent

of the individuals from those

groups could read in 1880, but by

1889, the number reached 18 percent.

In the Dakotas alone, nearly a quarter

of Native Americans could read English

or the Dakota language in 1890,

compared to only five percent

ten years earlier. Despite the emphasis on English

education, a significant percentage of

those

Plains Natives who could read did so only in their Native language.

Many Siouan-speaking

people

(Dakotas, Omahas, Poncas) took advantage

of their early contact with missionaries. Eastern Dakotas (Santees and Sissetons),

Western Dakotas (Yanktons and Yanktonai), and Lakotas were

all

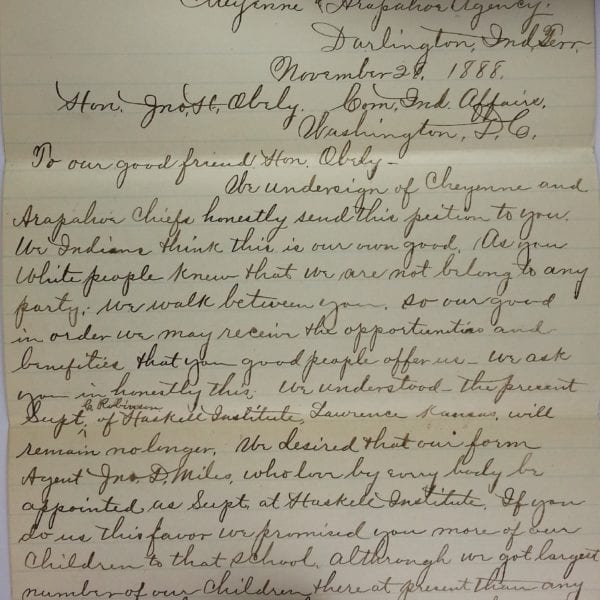

taught to write Dakota. Many communicated with one another using both

written Dakota and English.

However, several languages, including Kiowa,

Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Shoshoni, did not have a written form until

the twentieth century. These

groups relied on English.