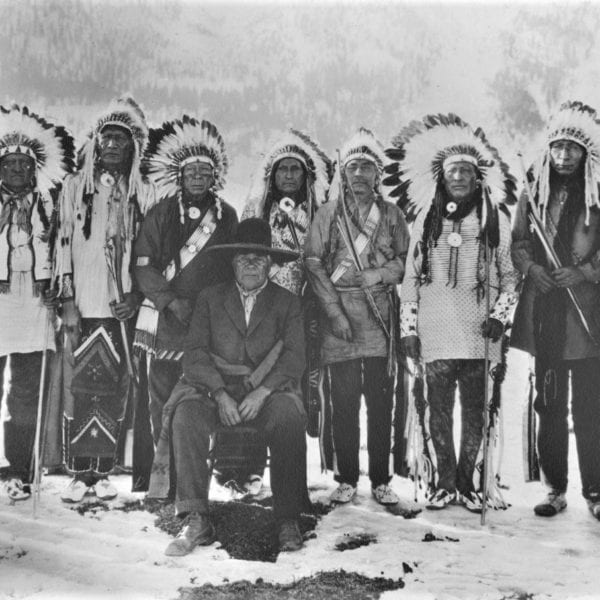

Wovoka, in the years following his revelation, received letters from distant

Indian groups in “considerable numbers.” Ed A. Dyer, who operated

a general store in Mason Valley, frequently translated and answered these

letters. Dyer stated that many were

from Grant Left Hand and postmarked

Darlington, Oklahoma, home of the Cheyenne-Arapaho

Agency. Left Hand

seemed to be a “scribe for most of the Indian Nations” as he invariably

sought invitations for others

to see Wovoka. He also requested multiple

sacred items from Wovoka, who made a habit of sending visiting delegates

back with balls of red ochre, magpie feathers, rabbit furs, and other religious

tokens. This led others

to want balls of red ochre of their own, and Wovoka

obliged, sending and usually selling the paint balls, magpie feathers, and

items of his worn clothing, particularly shirts and hats. Just as Sears Roebuck

was ramping up its mail order business, Wovoka was selling a great

many “Texas Plaza Hats” for twenty dollars apiece and shipping them 1,500

miles through the United States Postal Service.

The “Father,”

as the letters

addressed him, received all kinds of gifts of “Indian finery”: moccasins,

vests, gloves, shirts, pants, and headdresses, particularly from Bannocks in Idaho. Wovoka, with the aid of Dyer, would reply with gratitude and most

likely a word or two about his dance.

However, Wovoka, for a time, responded to these

letters with unusual

secrecy. He would sneak into Dyer’s grocery store at night, have the letters

read to him, and have Dyer prepare the proper packages in response. In

the fall of 1892, Agent C. C. Warner at the Nevada Agency grew concerned

with claims from the press that Wovoka was having “an evil influence” on

the Indians who visited him. The Silver State reported that Wovoka had

sent “emissaries” to Fort Hall, “urging them to inaugurate ghost dances

and prepare for war this spring.” Wovoka knew the negative attention his activities were

drawing.