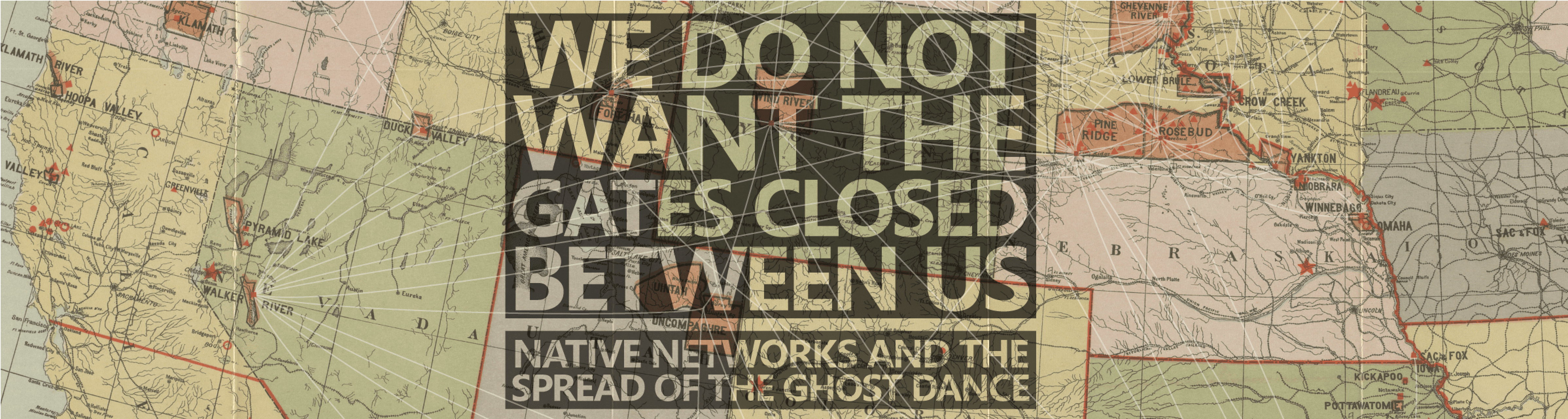

In the 1860s and 1870s, after years of resistance, most western Native Americans were forced to settle onto ever-shrinking pieces of land created by the United States government to relocate, contain, and separate

them. Native Americans were colonized peoples living on reservations, which, the US government hoped, would keep them away from each other and from the white populations coursing through the Plains. Despite this colonial control and confinement, Native Americans were able to remain mobile in the late nineteenth century.

This tenacious mobility, defined not only as the freedom of geographic movement but also the ability to share ideas and information widely, allowed western Native Americans to create vast networks of communication that traversed the boundaries of the US government’s reservations. These intertribal networks, threaded together in the 1870s and 1880s by intertribal visiting and letter writing, facilitated the dissemination of important information and ideas to Natives on a continental scale, often in opposition to US colonialism, including religious knowledge and practices like the Ghost Dance.