Natives also wrote to combat the glorified colonial narrative that filled newspapers across America. An Indian named John Daylight (Masse-Hadjo) wrote a letter to the Chicago Tribune defending the Ghost Dance movement. Responding to an editor who mocked the movement, Daylight presented a blistering critique of American Christianity, accusing whites of hypocrisy and cruelty. From the Quapaw Mission in Indian Territory, he argued that the Indians’ religion was superior to the white man’s because it was peaceful and uncorrupted. It was “adapted” to the Indians’ “wants.” He continued: “If our Messiah does come we shall not try to force you into our belief. We will never burn innocent women at the stake or pull men to pieces with horses because they refuse to join in our ghost dances. . . . You are anxious to get hold of our Messiah so you can put him in irons.” Daylight’s letter was reprinted in papers throughout the country; the Sacramento Daily said it ranked with the “speeches of Tecumseh, Phillip, Black Hawk and Logan” for its “pathos and satire and rhetorical eloquence.”

While information about the movement reached thousands of Native Americans, not all of them were convinced. In fact, the large majority of those who learned about the Ghost Dance movement did not become devoted dancers. Many actually criticized the movement and some put their criticism onto paper. Others made an effort to inform their communities about the movement, even if they themselves did not believe in it, thus helping to spread the dance. Sometime in 1890, Abe Somers, a twenty-two- year- old Southern Cheyenne who had spent five years at Carlisle, visited the Northern Cheyennes at the Tongue River Reservation in Montana, became a trusted interpreter for the Northerners, and learned about the Ghost Dance from Porcupine and his cousin Ridge Walker (Walker had also visited Wovoka). Somers wrote plainly about Porcupine’s beliefs in a statement to Native students the Haskell Institute, particularly those about non-violence, but he also urged them not to “follow the ideas of that man. He is not the Christ.” Somers was not a proponent of the dance, but he communicated its meaning to others; he was a relay, and some found truth in the message. James Murie, a Hampton graduate of both Pawnee and white descent who became an important ethnologist, also had a complicated experience with the Ghost Dance. He took part in the dances at the Pawnee Reservation in late 1891 and wrote to the Pawnee agent about it, explaining his participation and what he saw as the good and bad. The letter demonstrates the need some felt to experience the dance before judging its significance.

Division grew at the Lakota agencies between the believers and the nonbelievers. Some nonbelievers, worried that continued dancing would only provoke a harsh reaction from the US government, began telling federal authorities what they thought was happening at the Lakota reservations. At Standing Rock, Thomas Ashley, a twenty-three- year- old Hampton graduate, was disappointed that the Ghost Dance was affecting his people. “I am sorry to say some of us do not use all our education,” he wrote to his agent. Some Lakota dancers, however, blamed nonbelieving progressives for intentionally misrepresenting the Ghost Dance as a possibly violent militant movement to their agents with the hope that dancing would be suppressed. Issowonie, an Oglala, told Short Bull that his own people’s lies about the dance “caused the soldiers to come here.” Ring Thunder, a Brulé headman at Rosebud who did not believe in the dance, was sent by his agent in the fall 1890 to counsel with the dancers at Black Pipe Creek to try to convince them to stop. But the dancers would not listen to Ring Thunder, and they called him a fool. According to Ring Thunder’s letter to his former agent Lebbeus Foster Spencer, they told him that if he joined them, he “would never have any more pain or sorrow,” but if he “followed after the ways of the white men,” his “path would be hard and full of trouble.” But Ring Thunder told the dancers that he had once been “one of their bravest warriors,” but he no longer wanted to fight; his heart was “not with them.”

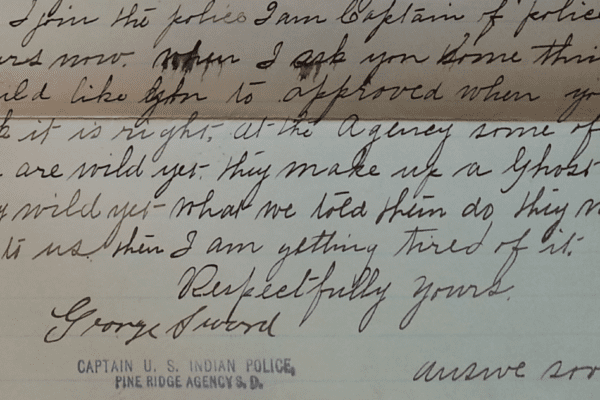

During November and December 1890, Lakota agency officials and the military attempted to quell the Ghost Dancing. Their targets were dancing camps far from agency offices that were holding out, ignoring US government instructions. Agents forwarded lists of the men they thought were most responsible for the trouble and whom they thought should be arrested. Eventually, after thorough negotiations between dancers, progressives, and white authorities, all would be forced to come into Pine Ridge to surrender. On December 6, E. G. Bettelyoun, an Oglala assistant clerk and former student at the Lincoln Institute in Philadelphia, described the atmosphere at Pine Ridge to his former teacher: “All the Indians of this Agency have quieted down. . . . I think all the papers are making it worse then it is.” Despite Bettelyoun’s optimism, the atmosphere at the Lakota agencies took a turn for the worse after the death of Sitting Bull (the Hunkpapa Lakota) at the hands of the Standing Rock Indian police on December 16, 1890. Sitting Bull refused to instruct his people to stop Ghost Dancing, a decision that angered his agent, James McLaughlin, who was already frustrated with Sitting Bull’s role in some of the illicit visitation that was occurring. At his own cabin, Sitting Bull and seven of his followers were killed during the arrest attempt. Lt. Bull Head and seven policemen also died. Skirmishes between the Indian police and members of Sitting Bull’s stunned band broke out immediately following the incident. The military tried to control the situation, but it only grew worse. Nearly five hundred men and women from Standing Rock fled their reservation out of fear and frustration.

Some from Sitting Bull’s camp ended up at Big Foot’s Miniconjou Ghost Dancing camp at Cherry Creek on the Cheyenne River Reservation; others made it to the dancing camps in the Badlands with Kicking Bear and Short Bull. The sight of traveling Indians frightened white settlers, especially the residents of Cheyenne City who abandoned their town. Members of the 12th Infantry were sent out to prevent Hunkpapas from joining Big Foot’s camp and the camps in the Badlands. They surrounded Big Foot’s camp, and with Hump serving as the mediator, the soldiers tried to persuade Big Foot’s people to return to Cheyenne River. Oglala leaders from Pine Ridge sent letters urging the holdouts in the Badlands to come in peacefully. They wrote to Big Foot, asking him to come into Pine Ridge to discuss the situation. A particular letter from Red Cloud, No Water, Big Road, and several others convinced the dancers to “join with the friendly Indians and help make peace.” Dewey Beard (Iron Hail), a Miniconjou Lakota Ghost Dancer who was twenty-two years old at the time, later recalled that the letter read, “My Dear Friend Chief Big Foot. Whenever you receive this letter I want you to come at once. Whenever you come to our reservation a fire is going to be started and I want you to come and help us to put it out and make a peace. Whenever you come among us to make a peace we will give you 100 head of horses.” Big Foot agreed and replied to the Pine Ridge headmen with a letter of his own. These communications gave hope that the crisis might end peacefully, but Lakotas still expressed a great deal of concern in their personal letters during the last days of the year, particularly about the conduct of the US soldiers.

On December 29, 1890, Big Foot’s Miniconjou band headed toward Pine Ridge to surrender, but they were confronted en route by the 7th Calvary, who had been ordered to disarm the people before they reached the agency. The Miniconjous, already afraid of military retribution, accepted disarmament, but a shot was fired during the tense process, and soldiers began firing into the crowd of men, women, and children. Soldiers chased the fleeing people, shooting many in the back, while machine guns positioned atop a hill blasted round after round. The official army report counted 176 Lakotas dead, but the actual number was undoubtedly higher. Just as they did after Sitting Bull’s death, Lakotas immediately wrote letters relaying news about the massacre at Pine Ridge. And like white Americans, Natives read about the massacre in the papers, but their reactions were much more empathetic than most whites’. Lakotas had “been treated shamefully,” John Half Iron (Santee) wrote to Herbert Welsh of the Indian Rights Association. He continued, “The officer of the war took all their guns and than shot into them with two Hotchkiss man women and children. My friend I don’t like that at all, and would like to know what you think about it. This is what I think. The Indians are ignorant and poor, But some whites are mean to them, they tries to take away what little they have. And when they took it all away from them they treat them poorly.”

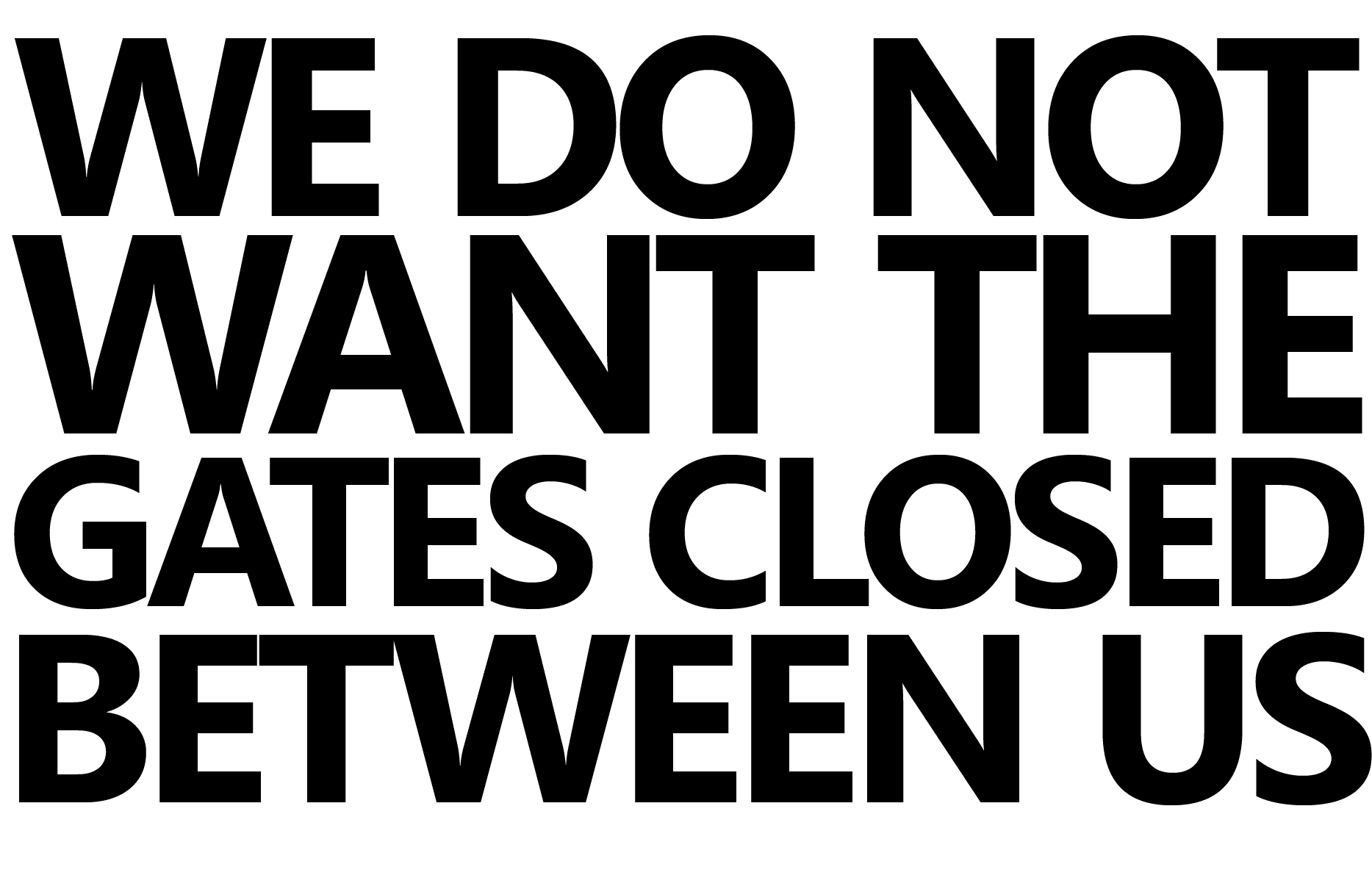

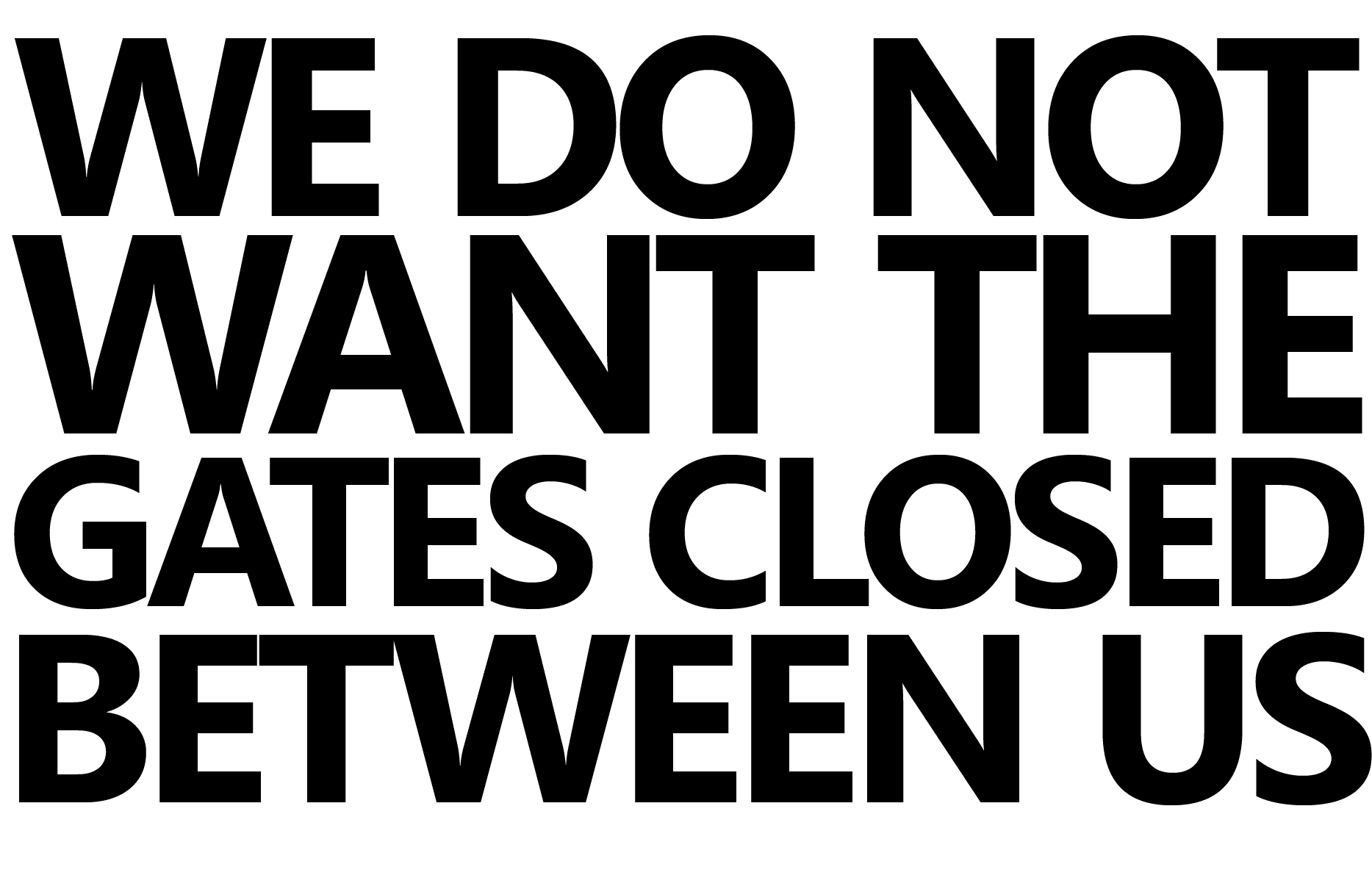

US officials also tried to control the narrative regarding the massacre, lying in at least one instance to Indians congregated at Cheyenne River about why women and children had been killed. Capt. Joseph Henry Hurst told the crowd that the barrage from the Hotchkiss and Gatling guns were intended for the five hundred hostile Brulés coming up Wounded Knee Creek toward the shooting, not the women and children fleeing for their lives; this was not true. The army would not admit the nature of the slaughter for fear of inspiring more resentment. Letter writing gave Lakotas a way to tell their own story, defend themselves, and kept themselves informed from sources outside US government control. Two Strike received letters from Indians at the Lower Brule Reservation and from “a young man from Standing Rock,” asking about the rumors of additional trouble. He told them that the Rosebud Brulés “were not going to make any more trouble and they must not pay attention to such talk. This talk gives me much trouble and I do not like it.” Other Lakota believers expressed their disappointment, writing that the true nature of their religion was never understood by whites and their US government. A group of Lakota headmen, who were about to head off as part of a delegation to Washington, DC, agreed to speak with the Washington Evening Star in late January. They knew the newspaper was published in the nation’s capital and hoped that politicians would read their side of the story. Big Road told the reporter that many Americans did not understand the movement “because the truth had not been told” to them.

Input your search keywords and press Enter.