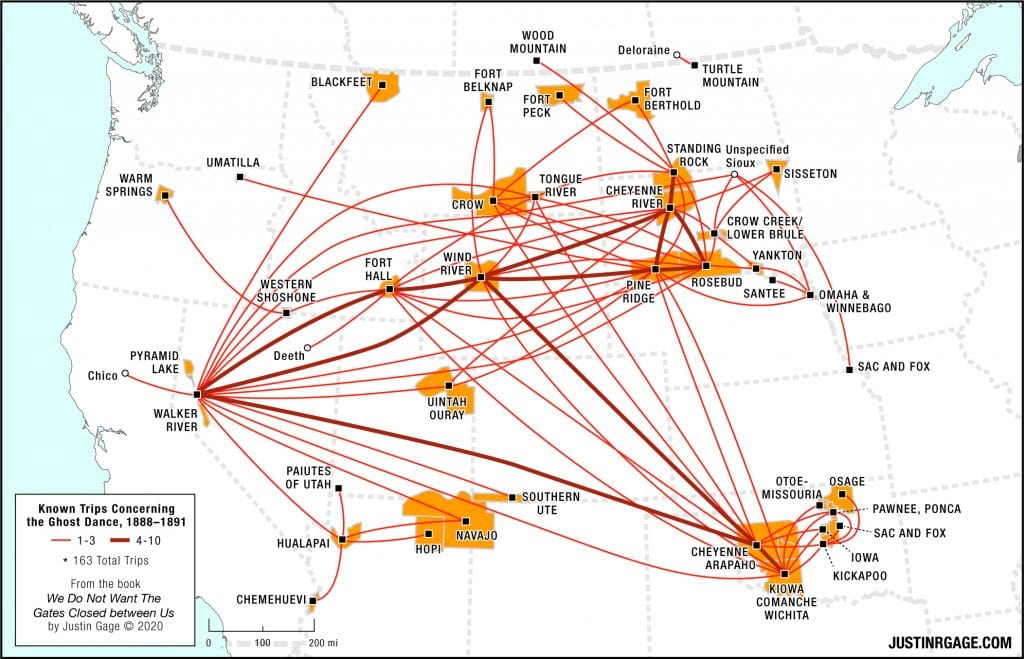

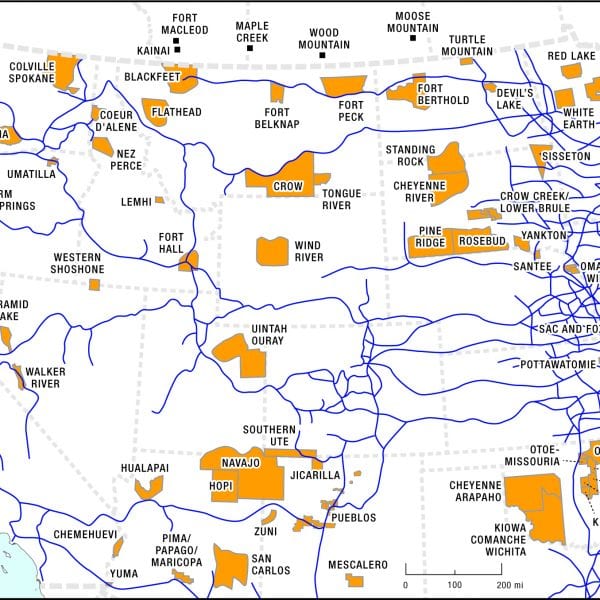

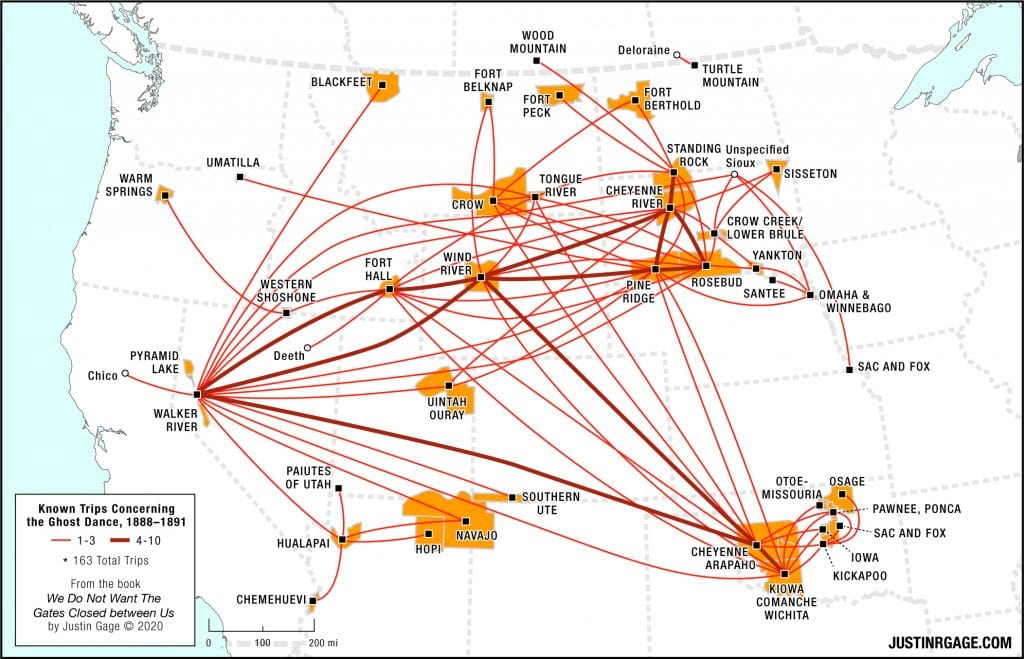

Out of western Nevada, through Fort Hall, and onto the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming Territory, information about the Ghost Dance spilled onto the Great Plains in 1889. From Wind River, the already-established networks of written correspondence spread that vision faster and farther. Sometime in 1889, Southern Arapaho chief Left Hand (the younger) received letters about a “second Jesus” from Wind River. Other Indians at the reservation, including Southern Cheyennes, began receiving similar correspondence in the summer of 1889 from Northern Arapahos at Wind River and from Northern Cheyennes at the Tongue River Reservation in Montana. Interested in the reports from his northern contacts, Left Hand and other headmen chose two men to travel and investigate the reports. In the meantime, Southern Arapahos and

Southern Cheyennes continued the investigation by sending out letters of inquiry. One of the interpreters at the agency, possibly Paul Boynton (Red Feather), a former student of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School of Cheyenne and Arapaho descent, wrote to the Northern Cheyennes at the Tongue River Agency in Montana. He wrote in part (in English), “Cheyennes and Arapahoes here are greatly excited about a Christ coming among some of the Northern tribes of Indians. The Arapahoes have been getting letters from Northern Arapahoes in regard to it. My friends here wish me to ask what there is about it, and what do you know about it?” The interpreter at Tongue River replied in part (also in English), “The Indians say Christ is in the mountains, and that he wants all the Indians to come to him.”

In 1889, Oglala Lakotas and Northern Cheyennes at the Pine Ridge Reservation began to receive messages about Wovoka in letters from Shoshones and Arapahos at Wind River. Other letters came from their recently established connection with Utes in Utah and other “distant agencies,” which relayed information “about the advent” of a “new Messiah.” In her history of her people, Josephine Waggoner wrote that “a new religion came by letters” to the Oglalas at Pine Ridge, who passed it along to other Lakotas. Waggoner, a then nineteen-year-old former Hampton student at Standing Rock, remembered reading “many letters” coming from both Pine Ridge and Walker River regarding the Ghost Dance. She translated correspondence for Sitting Bull (the Hunkpapa leader), among others, including letters about the new movement. William Selwyn, a literate Yankton employed at the time as postmaster at Pine Ridge, also read some of the letters for the Oglalas and Cheyennes there. According to Selwyn, there had been “some talk . . . about the New Messiah” in the fall of 1888 during visits from groups of Utes, Shoshones, Crows, and Arapahos, but the influx of letters from the western tribes in 1889 created “much attention” and convinced the Lakotas at Pine Ridge, Rosebud, and Cheyenne River to form a delegation to Walker River to investigate the claims.

The huge gathering at the Walker River Reservation in February and March 1890 was the product of all the information about the movement that was circulating across the West. Members of at least 39 tribal nations met at a place designated by Wovoka. At the height of the gathering, the Indian police at Walker River estimated 1,600 people were there to wait for Wovoka’s next appearance. The next day, Porcupine, a 41-year-old of both Lakota and Cheyenne descent who “had heard Christ had been crucified, noticed scars on Wovoka’s wrist and face, leading him to believe that Wovoka was the man they had heard about. The next morning, Wovoka assembled the people and sat down. Porcupine recounted how Wovoka told them that violence was the wrong approach, that it would be unnecessary because “the earth was to be all good hereafter, and we must all be friends with one another” and “that the whites and the Indians were to be all one people.” Porcupine said that Wovoka prophesized that in the fall of 1890, “the youth of all good people would be renewed, so that nobody would be more than 40 years old, and that if they behaved themselves well after this the youth of everyone would be renewed in the spring.” If “we were all good,” Porcupine recalled, Wovoka “would send people among us who could heal all our wounds and sickness by mere touch, and that we would live forever.”

The hundreds that gathered at Walker River in March 1890 listened to Wovoka for five days straight. On the fifth day, Short Bull, a Lakota from the Rosebud Reservation, shook hands with Wovoka, who only told him that “soon there would be no world, after the end of the world those who went to church would see all their relatives that had died. This will be the same all over the world even across the big waters.” Notably absent in the common current of the delegates’ interpretation were any violent ideas. Wovoka always emphasized peace and even taught that some features of the white world were fruitful. He told the people to “educate your children, send them to schools.” He relayed to the Lakotas, “Have your people work the ground . . . get farms.” Importantly, it may have been typical for a Paiute to have these opinions in the years before the Ghost Dance. According to a newspaper reporting on a Paiute Round Dance gathering in 1888, Paiute elders advised the young “to become farmers; to be truthful, honest, and industrious and sober.”

Input your search keywords and press Enter.