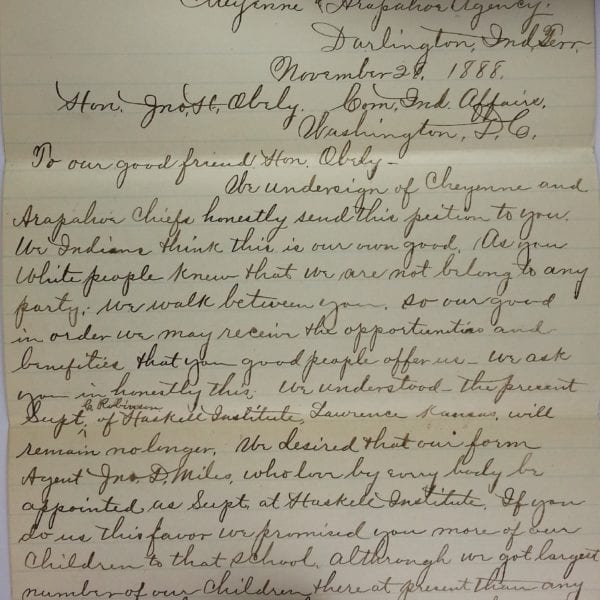

Before the 1870s, the large majority of Native Americans living west of the Mississippi (outside the so-called Five Civilized Tribes) and east of the Pacific coastal region had little opportunity to learn to read and write, despite many decades of contact with Europeans and Americans. Early missionaries to the eastern Plains began developing systems of writing as a way to get Indians to read the Bible in the 1830s, a normal route toward Indian conversion east of the Mississippi for two centuries. Catholic missionaries began educating Santees of the eastern Plains in the 1840s with Dakota-language prints of catechism, prayers, songs, and biblical messages. Missionary work did not begin in earnest in the western Plains until the reservation years of the 1870s, but Lakotas had begun using written text to their political advantage as early as 1846. In January

1846, sixteen Brulé and Oglala Lakota headmen made their marks on a petition to the president that asked for compensation for their loss of subsistence and for Lakotas “getting killed on several occasions” because of white encroachment.

Input your search keywords and press Enter.