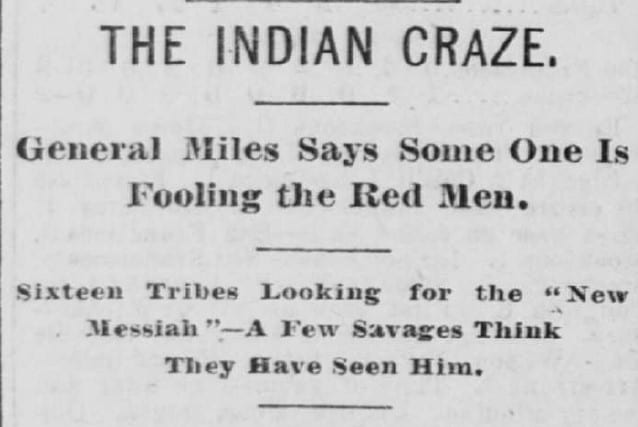

Unease about the Ghost Dance among US officials increased in late May 1890 because of a letter from an influential white settler named Charles L. Hyde of Pierre, South Dakota. Hyde, a large landowner and real estate dealer, informed the secretary of the interior that he had information, gathered from a confidential source, “that the Sioux Indians or a portion of them [were] secretly planning and arranging for an outbreak in the near future.” The Acting Commissioner of Indian Affairs called for a report from each of the agents at the Lakota reserves to “take prompt measures to ascertain whether there is any ground for apprehension,” but none of the agents thought there was much to Hyde’s warning. While Natives on several reservations were interested in the new Messiah and his message, there was not any evidence of planned violence. But Rosebud agent J. George Wright mentioned that “several secret communications” had been passed between the Lakota agencies in the previous months regarding the Indians’ “grievances against the Government.” Trouble began after a white cattleman was supposedly killed by some Cheyennes near the Tongue River Reservation (around Busby, Montana) around the same time that Porcupine assembled a large Ghost Dance at Tongue River. White settlers connected the two events, and the Cheyennes feared retribution, according to the Tongue River agent, R. L. Upshaw.

Agent Upshaw had the army arrest Porcupine in early June, but they later released him. Because he was spreading dangerous ideas, Upshaw recommended that Porcupine be placed under surveillance,

but if his “delusion” did not die and if he continued to “hold large gatherings to expand and propagate new revelations,” Upshaw thought he should be “sent to some other place.” For some, talk about the Messiah and a planned outbreak went hand in hand. Because of the content of the letters he read for the Oglalas and Northern Cheyennes in the spring of 1890, William Selwyn, the Yankton

postmaster at Pine Ridge, expected “a general Indian war” to break out in the spring of 1891. According to Selwyn, Wovoka prophesied that the return of the bison and the removal of the white man would occur in the spring of 1891. Selwyn assumed that some at Pine Ridge were creating “secret plans” over the “last one year or so” in preparation for that prophecy. Secrecy was a part of the movement for the Lakotas; their dance leaders were hesitant to share any information with white authorities. This secrecy created suspicion of communications, and whites distrusted dancers.

US officials would continue to use surveillance, spies, and informants to infiltrate Native networks. They also came to realize that letter writing needed to be controlled to halt the progress of the Ghost Dance. “These Indians communicate with each other through the mails to a great extent,” complained Charles Adams, the agent at the Kiowa, Comanche, and Wichita Agency, “and know by these means exactly how things are progressing in the land where this man is now convincing his followers that the white man must go, and that in the near future, nothing but Indians and buffalo will inhabit the earth.” So many letters about the Ghost Dance reached the Kiowa, Comanche, and Wichita Reservation that Agent Adams requested the power to censor the Indians’ mail. He wanted the postmaster general to instruct the postmaster at Anadarko, Oklahoma, to deliver all mail sent to the Indians into his hands for his “perusal.” He thought the Indians were “in an unsettled frame of mind” and that “steps should be taken to avoid future trouble.” For Adams, the solution was to prevent his population from communicating with the outside world. But Adams could do little to stop the letters from reaching Native eyes. Several weeks after Adams’s request, Maj. Wirt Davis reported that many of the Indians at the Kiowa, Comanche, and Wichita Reservation and at the Cheyenne-Arapaho Reservation could read and write and were receiving letters from friends and relatives at Pine Ridge, Tongue River, and Wind River.

The Ghost Dance continued to spread quickly in spring and early summer 1890, especially throughout Indian Territory, despite government efforts to limit intertribal visiting. Most camps at the Cheyenne-Arapaho Reservation were holding dances two to three times each week during that summer of 1890. In September, Southern Cheyenne runners invited all Kiowas, Comanches, Apaches, Wichitas, and probably others in Indian Territory to their reservation. Agent Ashley sent an urgent telegram to the Kiowa agent, asking him to “use all possible means to prevent” his Indians from leaving. Nevertheless, around three thousand Southern Cheyennes, Southern Arapahos, Kiowas, Caddos, Wichitas, and others gathered in September 1890 to dance under Sitting Bull’s direction or to witness the event. The Northern Arapaho Sitting Bull (not to be confused with the Lakota chief) became the leading proponent of the Ghost Dance at the Cheyenne-Arapaho Reservation. A lieutenant at Fort Sill called Sitting Bull “the most graceful sign talker” that he had ever met in the Southwest, which allowed him to communicate effectively between the peoples of the Great Basin and the Northern and Southern Plains. Sitting Bull did not think that Wovoka was Jesus, only a man who Jesus had “ ‘helped’ or inspired,” who told him that persevering in the dance would “cause sickness and death to disappear.” By December 1890, Maj. Wirt Davis was calling Sitting Bull “an apostle like St. Paul” who was “preaching the doctrine” off the Cheyenne-Arapaho Reservation to Kiowas, Apaches, Wichitas, and others in Indian Territory.

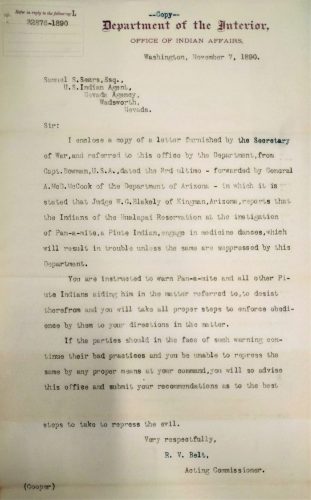

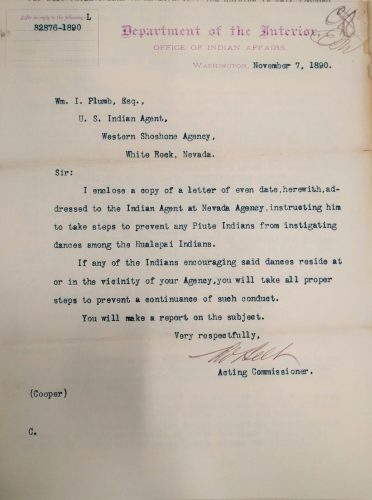

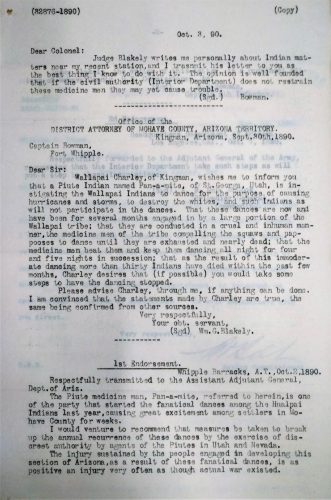

The US government also tried to curb visitation in order to break intertribal connections and thus stop the Ghost Dance’s spread. Agents already knew how hard it was to discourage intertribal dancing, and they learned just how intertribal in character the Ghost Dance was in the spring of 1890. Some agents were worried that their Indians would be contaminated with Ghost Dance ideology from foreign Indians; others were not. Some agents, especially those in Indian Territory, allowed the Indians under their charge to travel to other agencies to learn more about the dance, often fully aware of the purpose of the visits. Some US officials were confident that if people saw and heard Wovoka or other Ghost Dance apostles themselves, they would not believe their claims. Eventually, most agents realized that visitation only encouraged the dance’s spread. Down in Arizona, Indian affairs ordered Paiutes to stop visiting Hualapais after a visit from a Ghost Dance emissary named Panamite. The Commissioner of Indian Affairs considered the contact between Paiutes and Hualapais to be so dangerous that he asked the Paiute agent and agents in the vicinity to “repress” their dancing “by any proper means at your command.” Other agents west of the Rockies noticed a sharp rise in intertribal activity in the fall of 1890. Newspapers reported that dances were “more frequent than ever” in Nevada, with hundreds at the gatherings.

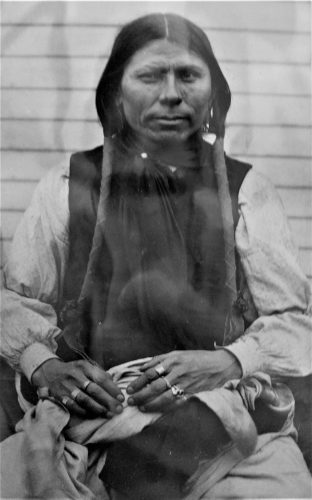

Intertribal visiting also circulated the dance in the Northern Plains. Movement continued between Wind River, Tongue River, and the Lakota agencies (Pine Ridge, Rosebud, Cheyenne River, and Standing Rock) in the summer and fall of 1890. A group of Pine Ridge Northern Cheyennes visited the Arapahos at Wind River in August 1890, for instance, and in October, some Wind River Northern Arapahos visited the Northern Cheyennes at Tongue River. Agents in South Dakota continued to arrest influential emissaries of the dance, hoping that time in the guardhouse might convince illicit travelers to stay home. Kicking Bear from Cheyenne River (who had kinship ties at Wind River), for instance, became a nuisance for a few agents there and was eventually arrested because of his desire to impart knowledge about the dance to other reservations. Kicking Bear’s continued exploits show the believers’ determination to spread the dance and ignore the barriers put up by the US government. By September 1890, perhaps one-quarter to one-third of the Lakotas at Pine Ridge, Rosebud, Cheyenne River, and Standing Rock were dance participants or believers or were seeking to learn more about the movement. One missionary at Rosebud estimated that 10 percent were dancing at Standing Rock, 15 percent at Cheyenne River, 30 percent at Rosebud, and 40 percent at Pine Ridge. Historian Jeffrey Ostler estimates that 4,000–5,000 Lakota were “involved” in the Ghost Dance (there were around 18,000 Lakotas on the reservations). At one dance along White Clay Creek at Pine Ridge, just eighteen miles north of agency headquarters, 2,000 had gathered (including spectators). Perhaps because of the surge in dancing, Lakota agents grew increasingly nervous in late summer, and one agent tried, without success, to use the Indian police to break up dancing.

Officials saw that the connections were energizing the Ghost Dance. According to a report from Brig. Gen. Thomas Ruger, all the dancing at Cheyenne River would have ended “had not the excitement been fed by Indians coming from other agencies, Pine Ridge and Rosebud in particular.” Ruger thought the agent had lost control. Because of the alarm of a new and inexperienced agent at Pine Ridge named D.F. Royer as well as the reports of dissent at other Lakota agencies, an inaccurate interpretation of the Lakota dance as a threat to civilian life, and the secretary of the interior’s concern, President Benjamin Harrison decided that the Ghost Dance deserved the government’s complete attention. Commissioner Morgan told the secretary of the interior that the situation at Pine Ridge was “very critical,” and because of Royer’s reports, he believed that an “outbreak” might be imminent. This created fear that the Ghost Dance could instigate rebellion on any reservation, especially if the “emissaries” were left unchecked. Even though it was clear that a minority of the Lakotas seemed disobedient, the military was eventually tasked to manage the situation. Troops were ordered to Pine Ridge and Rosebud in November 1890. Hundreds of Lakotas, believers and nonbelievers alike, left their camps in fear. A large group of Rosebud Brulés, perhaps two thousand, fled to the northern outskirts of Pine Ridge at Cuny Table in the Badlands, a camp that the military later called the Stronghold. Short Bull (who thought the soldiers were coming to Rosebud to kill him) and his followers were among those who camped there, refusing to give up the dance.

Measures were designed to stop the dancing, but they had little success. Directed by the commissioner of Indian affairs, agents across the West tried to prevent the Indians under their charge from having contact with Indians from other agencies. On November 22, 1890, the acting commissioner sent a circular letter to every agency office in the West. Because

it was “very important in view of the tendency of such excitement to spread and obtain a general hold upon the Indians,” he ordered agents to keep his office advised on their “condition of affairs” regarding the Ghost Dance. Officials saw the dance as a contagion that needed to be quarantined to the already-affected areas. Agent Simmons at the Fort Belknap Reservation thought it would be wise to use a cavalry company to “restrain” the outbreak of the dance by capturing “renegades” and the traveling “emissaries” of the movement. At the Lower Brule Reservation, Seventeen were

arrested “for participating in the ‘Ghost Dance’ and for endeavoring to induce others to engage therein . . . for disturbing the peace and mental attitudes of the Indians of that reserve,” and “for a general disobedience of orders of the Agent in charge of said reservation.”

Input your search keywords and press Enter.